Landing on Elixir: Pattern Matching

2021-08-01 Elixir pattern matchingAcknowledgements

I want to thank Po Chen for reviewing this post and providing valuable feedback.

- Landing on Elixir: Pattern Matching

- Landing on Elixir: Processing Immutable Data

Elixir is most likely not the first programming language for a programmer today. Most developers have previous programming experiences before using Elixir. Some come to this new place from OOP land. In such cases, to master programming in Elixir requires a shift of programming models. In this post, I will talk about some common patterns that can help new developers hone their Elixir skills.

Pattern matching is one of the most exciting features of a functional programming language. Functional programming features are being integrated into the mainstream programming languages so more and more programmers is getting familiar with functional languages features, including pattern matching.

What is pattern matching?

In Elixir, = is a match asserting operator instead of variable assigning. It takes left and right hand parts. If they match, the assertion is successful, and the result value of the expression is the right part.

iex> :foo = :foo

:foo

iex> [1, 2] = [1, 2]

[1, 2]

iex> %{foo: "bar"} = %{foo: "bar", foz: "baz"}

%{foo: "bar", foz: "baz"}

iex> %{} = %{a: 1}

%{a: 1}

Otherwise, it is considered unsuccessful and a MatchError will be raised:

iex> :foo = "foo"

** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: "foo"

iex> [1, 2] = [:a, :b]

** (MatchError) no match of right hand side value: [:a, :b]

Pattern matching has a side effect. If the left hand part has some unbind variable names, the corresponding matched values will be bound to them, respectively:

iex> {:ok, %{age: age, name: name}} = {:ok, %{age: 8, name: "Q"}}

{:ok, %{age: 8, name: "Q"}}

iex> age

8

iex> name

"Q"

There are a few things making it awesome.

Pattern matching makes our code expressive.

When we describe the requirement with pattern matching, we've almost finished programming. Let's take an example.

For example, someone asks us to buy something from the market on our way home:

If you come home early today, please buy some fruits and vegetables from the market. I need a bag of potatoes. Also, buy some apples and grapes if you see them.

Here's the code for it:

def what_to_buy(now, demands, item_seen) do

...

end

now = ~N[2021-08-01 20:45:12.623713]

demands = %{

"potato" => 1,

"apple" => :some,

"grape" => :some

}

items_seen = %{

"potato" => 0.5,

"apple" => 15

"egg" => 1

}

what_to_buy(now, demands, items_seen)

#=> %{

# "potato" => {:error, :sold_out},

# "apple" => {:ok, 2},

# "grape" => {:error, :not_seen}

# }

Now let's implement the function what_to_buy/3.

We may write something straightforward with the standard logic controls: if and cond.

def what_to_buy(now, demands, item_seen) do

unless too_late?(now) do

# Just incase if you wonder what this `into:` does:

# https://elixir-lang.org/getting-started/comprehensions.html#the-into-option

for {item, demand_quantity} <- demands, into: %{} do

cond do

item_seen[item] == nil ->

{item, {:error, :not_seen}}

not enough?(item_seen, item, demand_quantity) ->

{item, {:error, :sold_out}}

true ->

{item, {:ok, determine_quanity(item_seen, item, demand_quantity)}}

end

end

end

end

defp too_late?(t),

do: t.hour < 21

defp enough?(items_seen, item, demand_quanity) do

left = items_seen[item]

if demand_quanity == :some do

left > 0

else

left >= demand_quanity

end

end

defp determine_quanity(item_seen, item, demand_quanity) do

if demand_quanity == :some do

:rand.uniform(item_seen[item] - 1) + 1

else

demand_quanity

end

end

In constract, here's the pattern matching version:

defguard is_enough(left, x) when is_number(left) and is_number(x) and left >= x

defguard is_sold_out(left, x) when is_number(left) and is_number(x) and left < x

# first pattern: buy nothing when too late

def what_to_buy(%DateTime{hour: h}, _, _) when h > 21,

do: nil

def what_to_buy(_, demands, item_seen) do

for {item, demand_quanity} <- demands, into: %{} do

result =

case {item_seen[item], demand_quanity} do

# second pattern: available and demand is "some"

{left, :some} when is_number(left) ->

{:ok, :rand.uniform(left - 1) + 1}

# third pattern: available and fixed demanded quanlity

{left, x} when is_enough(left, x) ->

{:ok, x}

# fourth pattern: not enough on the market

{left, x} when is_sold_out(left, x) ->

{:error, :sold_out}

# fifth pattern: not seen on the market

{nil, _} ->

{:error, :not_seen}

end

{item, result}

end

end

As you can see, the pattern matching version is much easier to reflect the actual requirement.

And there's more about pattern matching.

Pattern matching is performant

because...

- Pattern matching will be optimized by compiler 1.

- Pattern matching can avoid creating temporary strings when matching on binaries 2.

Pattern matching is excellent at decomposing data structures

Here are some basic examples.

iex> [a, b | rest] = [1, 2, 3, 4]

...> a

1

iex> b

2

iex> rest

[3, 4]

Decomposing a nested map struct:

iex> response = %{

...> "data" => %{

...> "order1" => %{"success" => true}

...> }

...> }

...>

...> %{"data" => %{"order1" => %{"success" => succeeded}}} = response

...>

...> succeeded

true

Decomposing binary data:

iex> data = "\x03ABCfooooo"

...> <<content_len, "ABC", content::binary-size(content_len), _::binary>> = data

...> content_len

3

...> content

"foo"

Pattern matching makes decoding binary data so enjoyable. I love processing data in Elixir, and that's one of the fundamental reasons.

Special tip: pattern matching on lists

Some new developers think list in Elixir/Erlang as equivalent to Array in JavaScript. While an array has a length property that allows us to get its length efficiently, a list doesn't. The following code is considered inefficient:

# Do not do:

def handle_something(my_list) do

if length(my_list) > 0 do

do_something_with(my_list)

else

do_another_thing()

end

end

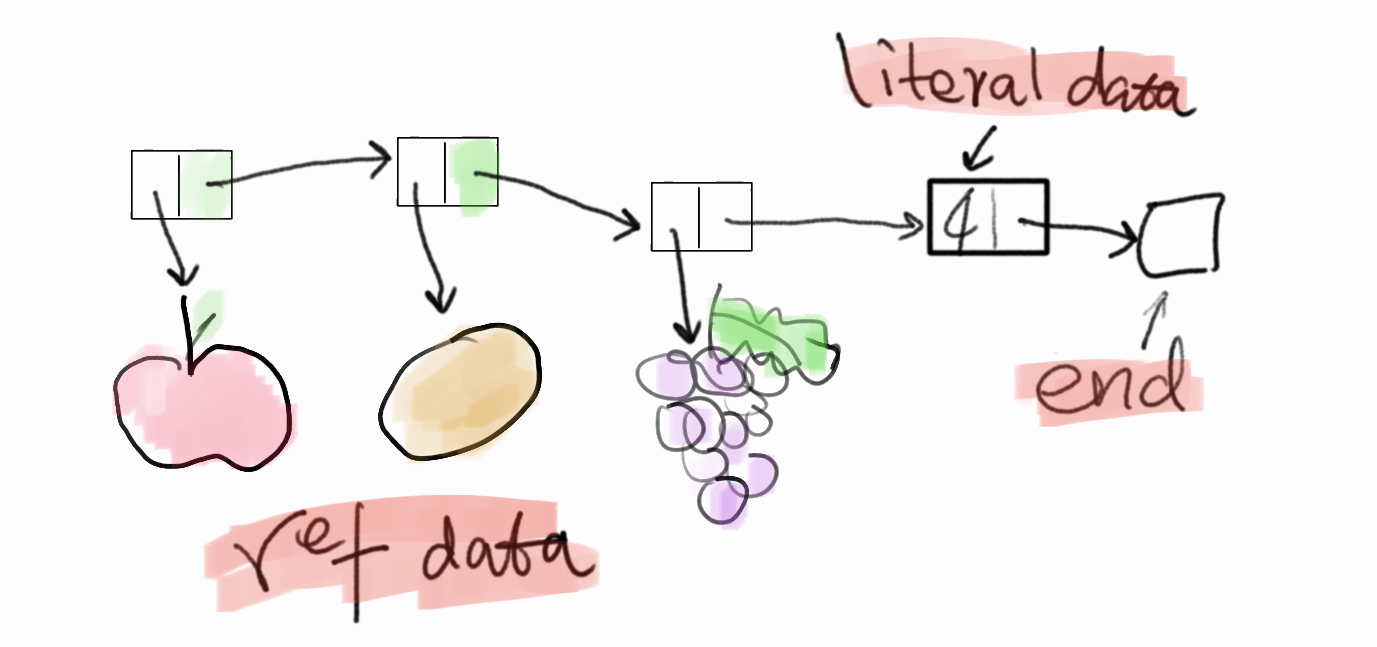

The problem is that lists are linked and sparse in memory. It's O(1) to get the head of the list or get the rest which is another list. When the rest is an empty list [], we know we have reached the end of the list. Getting the length of a list is of O(n) complexity of time.

So, we can rewrite the above example to:

def handle_something(my_list),

do: do_something_with(my_list)

defp do_something_with([]),

do: do_another_thing()

defp do_something_with([hd | rest]),

do: ...

There is a good article on this topic.

It is worth noting that pattern matching is the basis of recursion in Erlang.

def foo([_head | _tail]) # <- non_empty_list

def foo([]) # <- empty_list

This will lead us to an interesting topic: list and recursion. We'll talk about it later posts since this is already getting long.

Last tip: pattern matching on maps

%{} can match any map, not only empty maps.

if we want to match exactly an empty map, we can use == %{} guard. For example:

case my_map do

_ when my_map == %{} ->

"empty map"

%{} ->

"map"

_ ->

"other"

end

If we need to match an excatly non-empty map, we can employ Kernel.map_size/1 guard.

Update: I wrote another post on matching structs, instead of plain maps.

Conclusion

Pattern matching is something so powerful yet an enjoyable way to structure our code. In my opinion, it's one of the reasons why programming in Elixir or Erlang (or other functional programming languges) is so productive.

Further reading

- Official documentation on pattern matching

- Video tutorial of pattern matching in Elixir

- Pin operator for pattern matching

Comments